Portfolio/Case

Laksegade quarter

Transforming historic head quarter into new urban area

A new chapter

The doors are open to one of the most coveted locations in Copenhagen — perhaps even the country. Whether you’re looking for office space or retail, you’ll be surrounded by landmarks like Kongens Nytorv, Nyhavn, The Royal Theatre, Amalienborg and Christiansborg.

Sailors, vibrant nightlife, trading houses and financial institutions — the Laksegade Quarter has long been a stage for life, celebration, and major moments in both the city’s and the country’s history. Now, the transformation begins.

After nearly 150 years as home to Denmark’s major banks, Danske Bank — the last to remain — has moved out of its properties by Holmens Kanal. New owners have taken over: Thylander A/S, in partnership with real estate investor KanAm Grund Group and a German pension fund.

For decades, this area was reserved for bank employees and clients. But today, the doors are opening to everyone. In spring 2025, the transformation of the 16 buildings — comprising a total of 50,200 square meters — will begin, turning the area into a vibrant new neighborhood with shops, restaurants, cafés, offices, a hotel and a public parking facility.

The story of Laksegade begins with the sea

1600 — 1795

In 1795, a massive fire broke out at the shipyard at Bremerholm and spread rapidly to Laksegade, destroying large parts of the neighborhood. The devastation made room for new residents: merchants who had made fortunes through overseas trade — to such an extent that even the state came to them for loans. Their wealth gave rise to the grand mansions still standing today, including the iconic Erichsen Mansion, with its Ionic columns and prestigious address on Kongens Nytorv.

The city burns and the merchants move in

1795 — 1807

The fire gave way to new residents – the great merchants who made such a fortune from overseas trade that even the king came to the merchants to borrow money. This wealth made it possible to build the large mansions that still stand today, the most striking of which is Erichsen’s Palace, with its famous marble columns and location right next to Kongens Nytorv.

Trade declines, and banks take over

1872 – 1888

By the 19th century, trade began to falter, and the great fortunes diminished. The merchants moved out, and the banks moved in. The area around Nikolaj Plads and Holmens Kanal became the city’s financial hub, housing the National Bank and several of Denmark’s largest financial institutions. In spring 2024, Danske Bank’s departure marked the end of a 150-year chapter as Copenhagen’s banking district.

The Laksegade Quarter is being transformed

2025

In spring 2025, activity is returning to the streets, as Thylander A/S — in collaboration with engineers, contractors, local authorities and other partners — kicks off the redevelopment.

Over a three-year period, the neighborhood will be reshaped into a dynamic, open quarter — welcoming everyone back.

Our Listed Buildings Haven’t Always Led Peaceful Lives

1872 – 1888

The Laksegade Quarter — the former Danske Bank headquarters on Holmens Kanal — is full of listed buildings, though their history is anything but peaceful. Now, hidden details are once again being brought to light as part of Thylander and KanAm’s transformation of the area into a new, accessible urban district.

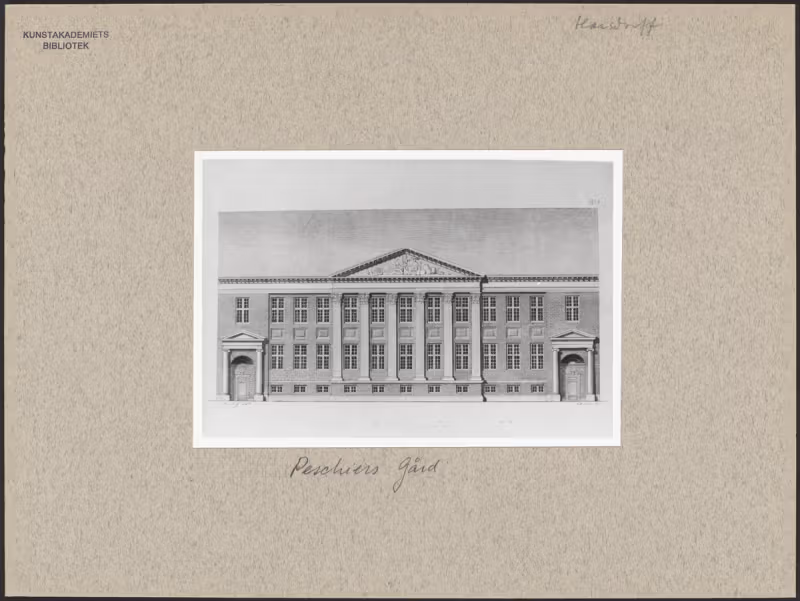

One of the great pleasures of redeveloping the Laksegade Quarter is working with its five listed buildings: Erichsen’s Palæ (familiar to most from its many appearances on newspaper front pages during the bank’s heyday), Grøn’s Gård, Peschier’s Gård and its Italian Renaissance-style extension at Holmens Kanal 14, and finally the smaller yet distinguished Skipperforeningens Hus, a fine example of Danish classicism.

Over their 225-year history, these buildings have undergone countless transformations, as successive owners have rebuilt and adapted them to meet the changing needs, functions, and aesthetic preferences of their times. Even after Denmark’s first building preservation law was passed in 1918 — which already listed several of these properties — the banks continued to make both major and minor alterations, with or without the approval of the preservation authorities.

Hidden Details Revealed

We have now carried out the careful removal of non-original structures at Peschier’s Gård and its extension at Holmens Kanal 14.

This included the removal of glued carpets, suspended ceilings with integrated lighting and ventilation systems, various floor constructions, and more — all with approval from the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces.

Although we already knew a great deal from old drawings, photographs, minor exploratory works, and even paintings, it is still a thrill to rediscover marble staircases, marble floor tiles, and decorative ceilings hidden behind later additions. These forgotten and partly original details are now being revived to form part of the current owners’ interpretation of a modern office environment within historic buildings.

From Harsdorff’s Classicism to the Opulence of Historicism

Peschier’s Gård, at Holmens Kanal 12, was built shortly after the Great Fire of Copenhagen in 1795 as a combined residence and commercial property for Danish businessman Pierre Peschier, who commissioned none other than C.F. Harsdorff, the era’s leading architect and Director of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

Harsdorff is known for a series of distinguished classical buildings — including our own Erichsen’s Palæ with its temple gable facing Kongens Nytorv, his own residence (Harsdorff’s Hus) on the same square, and even the temporary wooden colonnade connecting the palaces of Christian IX and Christian VII at Amalienborg, which, amusingly enough, still stands today.

About 50 years later, piano manufacturer Hornung (yes, the same one who later joined forces with Møller) acquired the property and needed more space. He commissioned architect G.F. Hetsch to add another storey. Hetsch must have approached the task with some reverence — his father-in-law (twice over, through both daughters!) was C.F. Hansen (of Copenhagen Cathedral and the Courthouse fame), who had been Harsdorff’s student and successor as Denmark’s leading classical architect. (Fortunately, the father-in-law had passed away five years earlier.)

Hetsch handled the challenge beautifully: he raised the roof, central risalit, pilasters, frontispiece with Roman gods, and all decorative elements by one storey, inserting a new ground floor beneath while keeping the two entrance portals in their original positions. The somewhat modest two-storey building was transformed into a proud three-storey palace — preserving all of Harsdorff’s original detailing.

Nearly 70 years later, the preservation authorities decided to list this “original” but technically unoriginal work.

When Landmandsbanken purchased the property in 1872, it soon outgrew the space and, just 16 years later, acquired and demolished the neighboring classical townhouse — then only about 80 years old — to make room for a savings bank branch and a boardroom. Architect H.B. Storck was commissioned to design an Italian Renaissance-style extension, lavishly decorated with a wide array of natural stones, colorful finishes, and ornamental details — a striking contrast to Harsdorff’s restrained Nordic classicism.

It may be no coincidence that this building wasn’t listed until more than 100 years after its completion — perhaps people needed some time to digest its exuberance.

Gentle Restoration – and New Uses

Later, Harsdorff’s refined classicism was obscured by extensive alterations to the grand hall — later known as the “Red Cabinet” — with wall-to-wall red carpets, floor-to-ceiling oak paneling (nicknamed “the Cigar Box”), the closure of the marble staircase between ground floor and basement, the installation of bank vaults, and more.

We are now carefully restoring the property together with our skilled heritage architects from Praksis and in close dialogue with the Agency for Culture and Palaces. Wherever possible, we bring forgotten architectural details back to life, restore where necessary, and add new structural elements to create a modern, functional workspace — with level-free access, open-plan offices, coffee stations, and, not least, a healthy indoor climate.

The listed buildings in the Laksegade Quarter continue their story through a new interpretation — and while their lives have never been peaceful, we hope they won’t become too quiet anytime soon.